Post by bluefedish on Jan 21, 2008 22:21:06 GMT -5

A Hindu goddess with a long and complex history in Hinduism. Although sometimes presented as dark and violent, her earliest incarnation as a figure of annihilation still has some influence, while more complex Tantric beliefs sometimes extend her role so far as to be the Ultimate Reality (Brahman) and Source of Being. She is also known and revered as Bhavatarini (meaning: redeemer of the universe Dakshineswar Kali Temple). Finally, the comparatively recent devotional movement largely conceives of Kali as a straightforwardly benevolent mother-goddess. Therefore, as with her association with the Deva (god) Shiva, Kali is associated with many Devis (goddessess) - Durga, Bhadrakali, Bhavani, Sati, Rudrani, Parvati, Chinnamasta, Chamunda, Kamakshi or Kamakhya, Uma, Meenakshi, Himavanti, Kumari and Tara. There names, if repeated, are believed to give special power to the worshipper. She is the formost Goddess among the Dasa Mahavidyas.

Kali appears in the Mundaka Upanishad (section 1, chapter 2, verse 4) not explicitly as a goddess, but as the black tongue of the seven flickering tongues of Agni, the Hindu god of fire. However, the prototype of the figure now known as Kali appears in the Rig Veda, in the form of a goddess named Raatri. Raatri is considered to be the prototype of both Durga and Kali.

In the Sangam era, circa 200BCE-200CE, of Tamilakam, a Kali-like bloodthirsty goddess named Kottravai appears in the literature of the period. Like Kali she has dishevelled hair, inspires fear in those who approach her and feasts on battlegrounds littered with the dead. It is quite likely that the fusion of the Sanskrit goddess Raatri and the indigenous Kottravai produced the fearsome goddesses of medieval Hinduism, Kali being the most prominent amongst them.

It was the composition of the Puranas in late antiquity that firmly gave Kali a place in the Hindu pantheon. Kali or Kalika is described in the Devi Mahatmya (also known as the Chandi or the Durgasaptasati) from the Markandeya Purana, circa 300-600CE, where she is said to have emanated from the brow of the goddess Durga, a slayer of demons or avidya, during one of the battles between the divine and anti-divine forces. In this context, Kali is considered the 'forceful' form of the great goddess Durga. Another account of the origins of Kali is found in the Matsya Purana, circa 1500CE, which states that she originated as a mountain tribal goddess in the north-central part of India, in the region of Mount Kalanjara (now known as Kalinjar). However this account is disputed because the legend was of later origin.

The Kalika Purana a work of late ninth or early tenth century, is one of the Upapuranas. The Kalika Purana mainly describes different manifestations of the Goddess, gives their iconographic details, mounts, and weapons. It also provides ritual procedures of worshipping Kalika.

Kali in Tantra Yoga

Goddesses play an important role in the study and practice of Tantra Yoga, and are affirmed to be as central to discerning the nature of reality as the male deities are. Although Parvati is often said to be the recipient and student of Shiva's wisdom in the form of Tantras, it is Kali who seems to dominate much of the Tantric iconography, texts, and rituals. In many sources Kali is praised as the highest reality or greatest of all deities. The Nirvnana-tantra says the gods Brahma, Vishnu, and Shiva all arise from her like bubbles in the sea, ceaslessly arising and passing away, leaving their original source unchanged. The Niruttara-tantra and the Picchila-tantra declare all of Kali's mantras to be the greatest and the Yogini-tantra , Kamakhya-tantra and the Niruttara-tantra all proclaim Kali vidyas (manifestations of Mahadevi, or "divinity itself"). They declare her to be an essence of her own form (svarupa) of the Mahadevi.

The figure of Kali conveys death, destruction, fear, and the consuming aspects of reality. As such, she is also a "forbidden thing", or even death itself. In the Pancatattva ritual, the sadhaka boldly seeks to confront Kali, and thereby assimilates and transforms her into a vehicle of salvation. This is clear in the work of the Karpuradi-stotra, a short praise to Kali describing the Panacatattva ritual unto her, performed on cremation grounds.

The Karpuradi-stotra clearly indicates that Kali is more than a terrible, vicious, slayer of demons who serves Durga or Shiva. Here, she is identified as the supreme mistress of the universe, associated with the five elements. In union with Lord Shiva, who is said to be her spouse, she creates and destroys worlds. Her appearance also takes a different turn, befitting her role as ruler of the world and object of meditation. In contrast to her terrible aspects, she takes on hints of a more benign dimension. She is described as young and beautiful, has a gentle smile, and makes gestures with her two right hands to dispel any fear and offer boons. The more positive features exposed offer the distillation of divine wrath into a goddess of salvation, who rids the sadhaka of fear. Here, Kali appears as a symbol of triumph over death.

Kali in Bengali Tradition

Kali is also central figure in late medieval Bengali devotional literature, with such devotees as Ramprasad Sen (1718-75). With the exception of being associated with Parvati as Shiva's consort, Kali is rarely pictured in Hindu mythology and iconography as a motherly figure until Bengali devotion beginning in the early eighteenth century. Even in Bengali tradition her appearance and habits change little, if at all.

The Tantric approach to Kali is to display courage by confronting her on cremation grounds in the dead of night, despite her terrible appearance. In contrast, the Bengali devotee appropriates Kali's teachings, adopting the attitude of a child. In both cases, the goal of the devotee is to become reconciled with death and to learn acceptance of the way things are. These themes are well addressed in Ramprasad's work.

Ramprasad comments in many of his other songs that Kali is indifferent to his wellbeing, causes him to suffer, brings his worldly desires to nothing and his worldly goods to ruin.

To be a child of Kali, Ramprasad asserts, is to be denied of earthly delights and pleasures. Kali is said to not give what is expected. To the devotee, it is perhaps her very refusal to do so that enables her devotees to reflect on dimensions of themselves and of reality that go beyond the material world.

A significant portion of Bengali devotional music features Kali as its central theme and is known as Shyama Sangeet. Mostly sung by male vocalists, today even women have taken to this form of music. One of the finest singers of Shyama Sangeet is Pannalal Bhattacharya.

Mythology

In Kali's most famous myth, Durga and her assistants, Matrikas, wound the demon Raktabija, in various ways and with a variety of weapons, in an attempt to destroy him. They soon find that they have worsened the situation, as for every drop of blood that is spilt from Raktabija the demon reproduces a copy of himself. The battlefield becomes increasingly filled with his duplicates. Durga, in dire need of help, summons Kali to combat the demons.

In Devi Mahatmya version of this story, Kali is also described as an Matrika and as a Shakti or power of Devi. She is given the epithet Câṃuṇḍâ (Chamunda) i.e the slayer of demons Chanda and Munda. Chamunda is very often identified with Kali and is very much like her in appearance and habit.

Daksinakali

In her most famous pose as Daksinakali, it is said that Kali, becoming drunk on the blood of her victims on the battlefield, dances with destructive frenzy. In her fury she fails to see the body of her husband Shiva who lies among the corpses on the battlefield. Ultimately the cries of Shiva attract Kali's attention, calming her fury. As a sign of her shame at having disrespected her husband in such a fashion, Kali sticks out her tongue. However, some sources state that this interpretation is a later version of the symbolism of the tongue: in tantric contexts, the tongue is seen to denote the element (guna) of rajas (energy and action) controlled by sattva, spiritual and godly qualities.

One South Indian tradition tells of a dance contest between Shiva and Kali. After defeating the two demons Sumbha and Nisumbha, Kali takes residence in a forest. With fierce companions she terrorizes the surrounding area. One of Shiva's devotees becomes distracted while doing austerities and asks Shiva to rid the forest of the destructive goddess. When Shiva arrives, Kali threatens him, claiming the territory as her own. Shiva challenges her to a dance contest, and defeats her when she is unable to perform the energetic Tandava dance. Although here Kali is defeated, and is forced to control her disruptive habits, we find very few images or other myths depicting her in such manner.

Maternal Kali

Another myth depicts the infant Shiva calming Kali, instead. In this similar story, Kali again defeated her enemies on the battlefield and began to dance out of control, drunk on the blood of the slain. To calm her down and to protect the stability of the world, Shiva is sent to the battlefield, as an infant, crying aloud. Seeing the child's distress, Kali ceases dancing to take care of the helpless infant. She picks him up, kisses his head, and proceeds to breast feed the infant Shiva. This myth depicts Kali in her benevolent, maternal aspect something that is revered in Hinduism, but not often recognized in the West.

Iconography

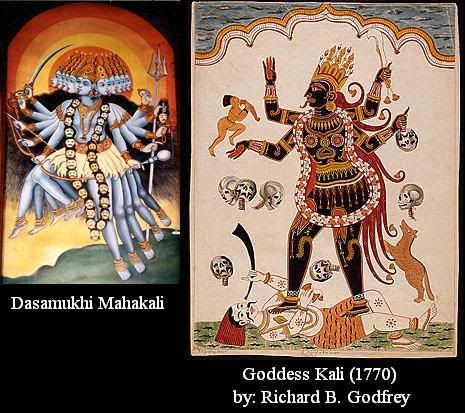

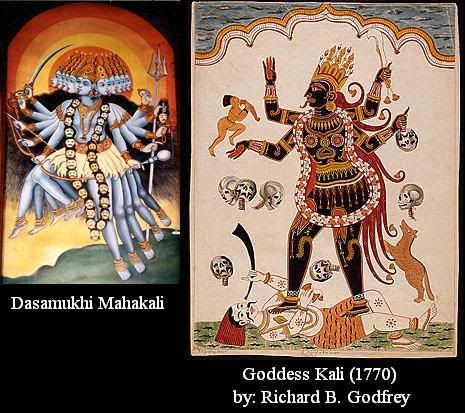

Kali is portrayed mostly in two forms: the popular four-armed form and the ten-armed Mahakali form. In both of her forms, she is described as being black in color but is most often depicted as blue in popular Indian art. Her eyes are described as red with intoxication and in absolute rage, Her hair is shown disheveled, small fangs sometimes protrude out of Her mouth and Her tongue is lolling. She is often shown naked or just wearing a skirt made of human arms and a garland of human heads. She is also accompanied by serpents and a jackal while standing on a seemingly dead Shiva, usually right foot forward to symbolize the more popular Dakshinamarga or right-handed path, as opposed to the more infamous and transgressive Vamamarga or left-handed path.

In the ten armed form of Mahakali she is depicted as shining like a blue stone. She has ten faces and ten feet and three eyes. She has ornaments decked on all her limbs. There is no association with Siva.

The Kalika Purana describes Kali as possessing a soothing dark complexion, as perfectly beautiful, riding a lion, four armed, holding a sword and blue lotuses, her hair unrestrained, body firm and youthful.

In spite of her seemingly terrible form, Kali is often considered the kindest and most loving of all the Hindu goddesses, as she is regarded by her devotees as the Mother of the whole Universe. And, because of her terrible form she is also often seen as a great protector. When the Bengali saint Ramakrishna once asked a devotee why one would prefer to worship Mother over him, this devotee rhetorically replied, “Maharaj, when they are in trouble your devotees come running to you. But, where do you run when you are in trouble?”

Throughout her history artists the world over have portrayed Kali in a myriad of poses and settings, some of which stray far from the popular description, and are sometimes even graphically sexual in nature. Given the popularity of this Goddess, artists everywhere will continue to explore the magnificence of Kali’s iconography. This is clear in the work of such contemporary artists as Charles Wish, and Tyeb Mehta, who sometimes take great liberties with the traditional, accepted symbolism, but still demonstrate a true reverence for the Shakta sect.

Popular form of Kali

Classic depictions of Kali share several features, as follows:

Kali's most common four armed iconographic image shows each hand carrying variously a sword, a trishul (trident), a severed head and a bowl or skull-cup (kapala) catching the blood of the severed head.

Two of these hands (usually the left) are holding a sword and a severed head. The Sword signifies Divine Knowledge and the Human Head signifies human Ego which must be slain by Divine Knowledge in order to attain Moksha. The other two hands (usually the right) are in the abhaya and varada mudras or blessings, which means her initiated devotees (or anyone worshiping her with a true heart) will be saved as she will guide them here and in the hereafter.

She has a garland consisting of human heads, variously enumerated at 108 (an auspicious number in Hinduism and the number of countable beads on a Japa Mala or rosary for repetition of Mantras) or 51, which represents Varnamala or the Garland of letters of the Sanskrit alphabet, Devanagari. Hindus believe Sanskrit is a language of dynamism, and each of these letters represents a form of energy, or a form of Kali. Therefore she is generally seen as the mother of language, and all mantras.

She is often depicted naked which symbolizes her being beyond the covering of Maya since she is pure (nirguna) being-consciousness-bliss and far above prakriti. She is shown as very dark as she is brahman in its supreme unmanifest state. She has no permanent qualities -- she will continue to exist even when the universe ends. It is therefore believed that the concepts of color, light, good, bad do not apply to her -- she is the pure, un-manifested energy, the Adi-shakti.

Mahakali Form

Kali is depicted in the Mahakali form as having ten heads, ten arms, and ten legs. Each of her ten hands is carrying a various implement which vary in different accounts, but each of these represent the power of one of the Devas or Hindu Gods and are often the identifying weapon or ritual item of a given Deva. The implication is that Mahakali subsumes and is responsible for the powers that these deities possess and this is in line with the interpretation that Mahakali is identical with Brahman. While not displaying ten heads, an "ekamukhi" or one headed image may be displayed with ten arms, signifying the same concept: the powers of the various Gods come only through Her grace.

Selected Source:

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maa_Kaali

Kali appears in the Mundaka Upanishad (section 1, chapter 2, verse 4) not explicitly as a goddess, but as the black tongue of the seven flickering tongues of Agni, the Hindu god of fire. However, the prototype of the figure now known as Kali appears in the Rig Veda, in the form of a goddess named Raatri. Raatri is considered to be the prototype of both Durga and Kali.

In the Sangam era, circa 200BCE-200CE, of Tamilakam, a Kali-like bloodthirsty goddess named Kottravai appears in the literature of the period. Like Kali she has dishevelled hair, inspires fear in those who approach her and feasts on battlegrounds littered with the dead. It is quite likely that the fusion of the Sanskrit goddess Raatri and the indigenous Kottravai produced the fearsome goddesses of medieval Hinduism, Kali being the most prominent amongst them.

It was the composition of the Puranas in late antiquity that firmly gave Kali a place in the Hindu pantheon. Kali or Kalika is described in the Devi Mahatmya (also known as the Chandi or the Durgasaptasati) from the Markandeya Purana, circa 300-600CE, where she is said to have emanated from the brow of the goddess Durga, a slayer of demons or avidya, during one of the battles between the divine and anti-divine forces. In this context, Kali is considered the 'forceful' form of the great goddess Durga. Another account of the origins of Kali is found in the Matsya Purana, circa 1500CE, which states that she originated as a mountain tribal goddess in the north-central part of India, in the region of Mount Kalanjara (now known as Kalinjar). However this account is disputed because the legend was of later origin.

The Kalika Purana a work of late ninth or early tenth century, is one of the Upapuranas. The Kalika Purana mainly describes different manifestations of the Goddess, gives their iconographic details, mounts, and weapons. It also provides ritual procedures of worshipping Kalika.

Kali in Tantra Yoga

Goddesses play an important role in the study and practice of Tantra Yoga, and are affirmed to be as central to discerning the nature of reality as the male deities are. Although Parvati is often said to be the recipient and student of Shiva's wisdom in the form of Tantras, it is Kali who seems to dominate much of the Tantric iconography, texts, and rituals. In many sources Kali is praised as the highest reality or greatest of all deities. The Nirvnana-tantra says the gods Brahma, Vishnu, and Shiva all arise from her like bubbles in the sea, ceaslessly arising and passing away, leaving their original source unchanged. The Niruttara-tantra and the Picchila-tantra declare all of Kali's mantras to be the greatest and the Yogini-tantra , Kamakhya-tantra and the Niruttara-tantra all proclaim Kali vidyas (manifestations of Mahadevi, or "divinity itself"). They declare her to be an essence of her own form (svarupa) of the Mahadevi.

The figure of Kali conveys death, destruction, fear, and the consuming aspects of reality. As such, she is also a "forbidden thing", or even death itself. In the Pancatattva ritual, the sadhaka boldly seeks to confront Kali, and thereby assimilates and transforms her into a vehicle of salvation. This is clear in the work of the Karpuradi-stotra, a short praise to Kali describing the Panacatattva ritual unto her, performed on cremation grounds.

The Karpuradi-stotra clearly indicates that Kali is more than a terrible, vicious, slayer of demons who serves Durga or Shiva. Here, she is identified as the supreme mistress of the universe, associated with the five elements. In union with Lord Shiva, who is said to be her spouse, she creates and destroys worlds. Her appearance also takes a different turn, befitting her role as ruler of the world and object of meditation. In contrast to her terrible aspects, she takes on hints of a more benign dimension. She is described as young and beautiful, has a gentle smile, and makes gestures with her two right hands to dispel any fear and offer boons. The more positive features exposed offer the distillation of divine wrath into a goddess of salvation, who rids the sadhaka of fear. Here, Kali appears as a symbol of triumph over death.

Kali in Bengali Tradition

Kali is also central figure in late medieval Bengali devotional literature, with such devotees as Ramprasad Sen (1718-75). With the exception of being associated with Parvati as Shiva's consort, Kali is rarely pictured in Hindu mythology and iconography as a motherly figure until Bengali devotion beginning in the early eighteenth century. Even in Bengali tradition her appearance and habits change little, if at all.

The Tantric approach to Kali is to display courage by confronting her on cremation grounds in the dead of night, despite her terrible appearance. In contrast, the Bengali devotee appropriates Kali's teachings, adopting the attitude of a child. In both cases, the goal of the devotee is to become reconciled with death and to learn acceptance of the way things are. These themes are well addressed in Ramprasad's work.

Ramprasad comments in many of his other songs that Kali is indifferent to his wellbeing, causes him to suffer, brings his worldly desires to nothing and his worldly goods to ruin.

To be a child of Kali, Ramprasad asserts, is to be denied of earthly delights and pleasures. Kali is said to not give what is expected. To the devotee, it is perhaps her very refusal to do so that enables her devotees to reflect on dimensions of themselves and of reality that go beyond the material world.

A significant portion of Bengali devotional music features Kali as its central theme and is known as Shyama Sangeet. Mostly sung by male vocalists, today even women have taken to this form of music. One of the finest singers of Shyama Sangeet is Pannalal Bhattacharya.

Mythology

In Kali's most famous myth, Durga and her assistants, Matrikas, wound the demon Raktabija, in various ways and with a variety of weapons, in an attempt to destroy him. They soon find that they have worsened the situation, as for every drop of blood that is spilt from Raktabija the demon reproduces a copy of himself. The battlefield becomes increasingly filled with his duplicates. Durga, in dire need of help, summons Kali to combat the demons.

In Devi Mahatmya version of this story, Kali is also described as an Matrika and as a Shakti or power of Devi. She is given the epithet Câṃuṇḍâ (Chamunda) i.e the slayer of demons Chanda and Munda. Chamunda is very often identified with Kali and is very much like her in appearance and habit.

Daksinakali

In her most famous pose as Daksinakali, it is said that Kali, becoming drunk on the blood of her victims on the battlefield, dances with destructive frenzy. In her fury she fails to see the body of her husband Shiva who lies among the corpses on the battlefield. Ultimately the cries of Shiva attract Kali's attention, calming her fury. As a sign of her shame at having disrespected her husband in such a fashion, Kali sticks out her tongue. However, some sources state that this interpretation is a later version of the symbolism of the tongue: in tantric contexts, the tongue is seen to denote the element (guna) of rajas (energy and action) controlled by sattva, spiritual and godly qualities.

One South Indian tradition tells of a dance contest between Shiva and Kali. After defeating the two demons Sumbha and Nisumbha, Kali takes residence in a forest. With fierce companions she terrorizes the surrounding area. One of Shiva's devotees becomes distracted while doing austerities and asks Shiva to rid the forest of the destructive goddess. When Shiva arrives, Kali threatens him, claiming the territory as her own. Shiva challenges her to a dance contest, and defeats her when she is unable to perform the energetic Tandava dance. Although here Kali is defeated, and is forced to control her disruptive habits, we find very few images or other myths depicting her in such manner.

Maternal Kali

Another myth depicts the infant Shiva calming Kali, instead. In this similar story, Kali again defeated her enemies on the battlefield and began to dance out of control, drunk on the blood of the slain. To calm her down and to protect the stability of the world, Shiva is sent to the battlefield, as an infant, crying aloud. Seeing the child's distress, Kali ceases dancing to take care of the helpless infant. She picks him up, kisses his head, and proceeds to breast feed the infant Shiva. This myth depicts Kali in her benevolent, maternal aspect something that is revered in Hinduism, but not often recognized in the West.

Iconography

Kali is portrayed mostly in two forms: the popular four-armed form and the ten-armed Mahakali form. In both of her forms, she is described as being black in color but is most often depicted as blue in popular Indian art. Her eyes are described as red with intoxication and in absolute rage, Her hair is shown disheveled, small fangs sometimes protrude out of Her mouth and Her tongue is lolling. She is often shown naked or just wearing a skirt made of human arms and a garland of human heads. She is also accompanied by serpents and a jackal while standing on a seemingly dead Shiva, usually right foot forward to symbolize the more popular Dakshinamarga or right-handed path, as opposed to the more infamous and transgressive Vamamarga or left-handed path.

In the ten armed form of Mahakali she is depicted as shining like a blue stone. She has ten faces and ten feet and three eyes. She has ornaments decked on all her limbs. There is no association with Siva.

The Kalika Purana describes Kali as possessing a soothing dark complexion, as perfectly beautiful, riding a lion, four armed, holding a sword and blue lotuses, her hair unrestrained, body firm and youthful.

In spite of her seemingly terrible form, Kali is often considered the kindest and most loving of all the Hindu goddesses, as she is regarded by her devotees as the Mother of the whole Universe. And, because of her terrible form she is also often seen as a great protector. When the Bengali saint Ramakrishna once asked a devotee why one would prefer to worship Mother over him, this devotee rhetorically replied, “Maharaj, when they are in trouble your devotees come running to you. But, where do you run when you are in trouble?”

Throughout her history artists the world over have portrayed Kali in a myriad of poses and settings, some of which stray far from the popular description, and are sometimes even graphically sexual in nature. Given the popularity of this Goddess, artists everywhere will continue to explore the magnificence of Kali’s iconography. This is clear in the work of such contemporary artists as Charles Wish, and Tyeb Mehta, who sometimes take great liberties with the traditional, accepted symbolism, but still demonstrate a true reverence for the Shakta sect.

Popular form of Kali

Classic depictions of Kali share several features, as follows:

Kali's most common four armed iconographic image shows each hand carrying variously a sword, a trishul (trident), a severed head and a bowl or skull-cup (kapala) catching the blood of the severed head.

Two of these hands (usually the left) are holding a sword and a severed head. The Sword signifies Divine Knowledge and the Human Head signifies human Ego which must be slain by Divine Knowledge in order to attain Moksha. The other two hands (usually the right) are in the abhaya and varada mudras or blessings, which means her initiated devotees (or anyone worshiping her with a true heart) will be saved as she will guide them here and in the hereafter.

She has a garland consisting of human heads, variously enumerated at 108 (an auspicious number in Hinduism and the number of countable beads on a Japa Mala or rosary for repetition of Mantras) or 51, which represents Varnamala or the Garland of letters of the Sanskrit alphabet, Devanagari. Hindus believe Sanskrit is a language of dynamism, and each of these letters represents a form of energy, or a form of Kali. Therefore she is generally seen as the mother of language, and all mantras.

She is often depicted naked which symbolizes her being beyond the covering of Maya since she is pure (nirguna) being-consciousness-bliss and far above prakriti. She is shown as very dark as she is brahman in its supreme unmanifest state. She has no permanent qualities -- she will continue to exist even when the universe ends. It is therefore believed that the concepts of color, light, good, bad do not apply to her -- she is the pure, un-manifested energy, the Adi-shakti.

Mahakali Form

Kali is depicted in the Mahakali form as having ten heads, ten arms, and ten legs. Each of her ten hands is carrying a various implement which vary in different accounts, but each of these represent the power of one of the Devas or Hindu Gods and are often the identifying weapon or ritual item of a given Deva. The implication is that Mahakali subsumes and is responsible for the powers that these deities possess and this is in line with the interpretation that Mahakali is identical with Brahman. While not displaying ten heads, an "ekamukhi" or one headed image may be displayed with ten arms, signifying the same concept: the powers of the various Gods come only through Her grace.

Selected Source:

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maa_Kaali