Post by bluefedish on Jan 11, 2008 12:38:38 GMT -5

The Book of Kells (Irish: Leabhar Cheanannais) (Dublin, Trinity College Library, MS A. I. (58), less widely known as the Book of Columba) is an ornately illustrated manuscript, produced by Celtic monks around AD 800 in the style known as Insular art.

The Book of Kells is an illuminated manuscript that has survived from the Middle Ages and has been described as the zenith of Western calligraphy and illumination. It contains the four gospels of the Bible in Latin, along with prefatory and explanatory matter decorated with numerous colourful illustrations and illuminations. Today it is on permanent display at the Trinity College Library in Dublin, Ireland.

Origin

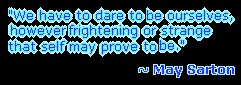

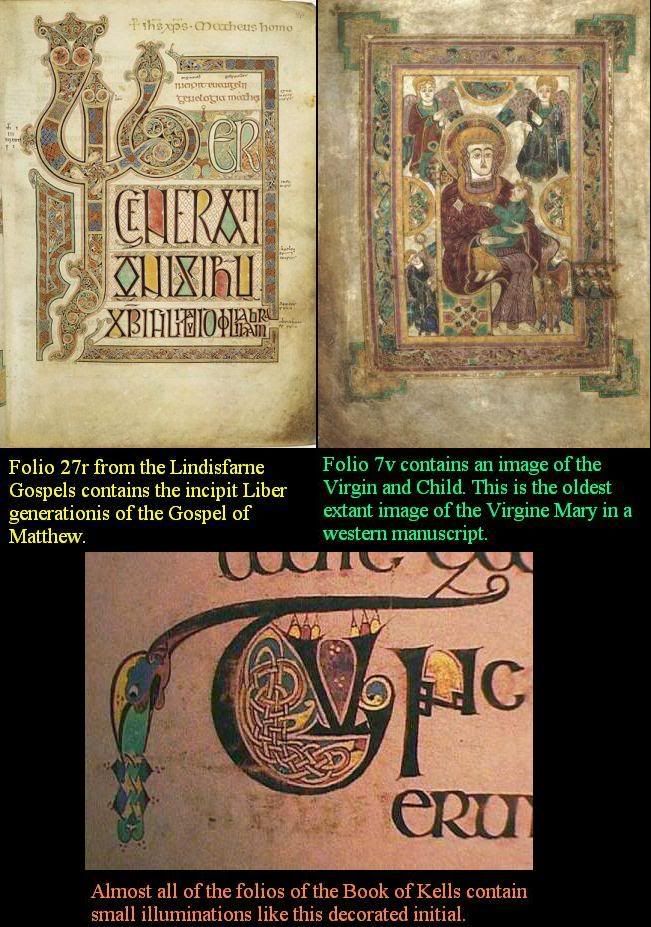

The Book of Kells is the high point of a group of manuscripts in what is known as the Insular style produced from the late 6th through the early 9th centuries in monasteries in Ireland, Scotland and northern England and in continental monasteries with Irish or English foundations. These manuscripts include the Cathach of St. Columba, the Ambrosiana Orosius, a fragmentary gospel in the Durham cathedral library (all from the early 7th century), and the Book of Durrow (from the second half of the 7th century). From the early 8th century come the Durham Gospels, the Echternach Gospels, the Lindisfarne Gospels (see illustration at right), and the Lichfield Gospels. The St. Gall Gospel Book and the Macregal Gospels come from the late 8th century. The Book of Armagh (dated to 807–809), the Turin Gospel Book Fragment, the Leiden Priscian, the St. Gall Priscian and the Macdurnan Gospel all date from the early 9th century. Scholars place these manuscripts together based on similarities in artistic style, script, and textual traditions. The fully developed style of the ornamentation of the Book of Kells places it late in this series, either from the late eighth or early ninth century. The Book of Kells follows many of the iconographic and stylistic traditions found in these earlier manuscripts. For example, the form of the decorated letters found in the incipit pages for the Gospels is surprisingly consistent in Insular Gospels. Compare, for example, the incipit pages of the Gospel of Matthew in the Lindisfarne Gospels and in the Book of Kells both of which feature intricate decorative knotwork inside the outlines formed by the enlarged initial letters of the text.

The name "Book of Kells" is derived from the Abbey of Kells in Kells, County Meath in Ireland, where it was kept for much of the medieval period. The date and place of production of the manuscript has been the subject of considerable debate. Traditionally, the book was thought to have been created in the time of Columba (also known as St Columcille), possibly even as the work of his own hands. However, it is now generally accepted that this tradition is false based on palaeographic grounds: the style of script in which the book is written did not develop until well after Columba's death, making it impossible for him to have written it. Evidence shows the Book of Kells was written around the year 800 AD. There is another tradition which has some traction among Irish scholars which suggests that it was created for the 200th anniversary of the saint's death.

The manuscript was never finished. There are at least five competing theories about the manuscript's place of origin and time of completion. First, the book may have been created entirely at Iona, then brought to Kells and never finished. Second, the book may have been begun at Iona and continued at Kells, but never finished. Third, the manuscript may have been produced entirely in the scriptorium at Kells. Fourth, it may have been produced in the north of England, perhaps at Lindisfarne, then brought to Iona and from there to Kells. Finally, it may have been the product of an unknown monastery in Scotland. Although the question of the exact location of the book's production will probably never be answered conclusively, the second theory, that it was begun at Iona and finished at Kells, is currently the most widely accepted. Regardless of which theory is true, it is certain that the Book of Kells was produced by Columban monks closely associated with the community at Iona.

Medieval Period

The evidence for an eleventh century presence of the book in Kells consists of an entry in the Annals of Ulster for 1009. This entry records that "the great Gospel of Columkille, the chief relic of the Western World, was wickedly stolen during the night from the western sacristy of the great stone church at Cenannas on account of its wrought shrine". Cenannas is the Irish name for Kells. The manuscript was recovered a few months later - minus its golden and bejewelled cover - "under a sod". It is generally assumed that the "great Gospel of Columkille" is the Book of Kells. If this is correct, then the book was in Kells by 1009, and been there long enough for thieves to learn of its presence. The force of ripping the manuscript free from its cover may account for the folios missing from the beginning and end of the Book of Kells.

Regardless, the book was certainly at Kells in the 12th century, when land charters pertaining to the Abbey of Kells were copied into some of the book's blank pages. The copying of charters into important books such as the Book of Kells was a wide-spread mediaeval practice, which gives us indisputable evidence about the location of the book at the time the charters were written into it.

The Abbey of Kells was dissolved due to the ecclesiastical reforms of the 12th century. The abbey church was converted to a parish church in which the Book of Kells remained.

Book of Kildare

The 12th century writer, Gerald of Wales, in his Topographia Hibernica, described, in a famous passage, seeing a great Gospel Book in Kildare which many have since assumed was the Book of Kells. The description certainly matches Kells:

"This book contains the harmony of the Four Evangelists according to Jerome, where for almost every page there are different designs, distinguished by varied colours. Here you may see the face of majesty, divinely drawn, here the mystic symbols of the Evangelists, each with wings, now six, now four, now two; here the eagle, there the calf, here the man and there the lion, and other forms almost infinite. Look at them superficially with the ordinary glance, and you would think it is an erasure, and not tracery. Fine craftsmanship is all about you, but you might not notice it. Look more keenly at it and you will penetrate to the very shrine of art. You will make out intricacies, so delicate and so subtle, so full of knots and links, with colours so fresh and vivid, that you might say that all this was the work of an angel, and not of a man."

Since Gerald claims to have seen this book in Kildare, he may have seen another, now lost, book equal in quality to the Book of Kells, or he may have misstated his location.

Modern Period

The Book of Kells remained in Kells until 1654. In that year Cromwell's cavalry was quartered in the church at Kells and the governor of the town sent the book to Dublin for safe keeping. The book was presented to Trinity College in Dublin in 1661 by Henry Jones, who was to become bishop of Meath after the Restoration. The book has remained at Trinity College since the 17th century, except for brief loans to other libraries and museums. It has been displayed to the public in the Old Library at Trinity since the 19th century.

In the 16th century, the chapter numbers of the Gospels according to the division created by the 13th century Archbishop of Canterbury, Stephen Langton were written in the margins of the pages in roman numerals by Gerald Plunkett of Dublin. In 1621 the folios were numbered by the bishop-elect of Meath, James Ussher. In 1849 Queen Victoria and Prince Albert were invited to sign the book. They in fact signed a modern flyleaf which was erroneously believed to have been one of the original folios. The page which they signed was removed when the book was rebound in 1953.

Over the centuries the book has been rebound several times. During an 18th century rebinding, the pages were rather unsympathetically cropped, with small parts of some illustrations being lost. The book was also rebound in 1895, but that rebinding broke down quickly. By the late 1920s several folios were being kept loose under a separate cover. In 1953, the work was bound in four volumes by Roger Powell, who also gently stretched several of the pages, which had developed bulges.

In 2000, the volume containing the Gospel of Mark was sent to Canberra, Australia for an exhibition of illuminated manuscripts. This was only the fourth time the Book of Kells had been sent abroad for exhibition. Unfortunately, the volume suffered what has been called "minor pigment damage" while en route to Canberra. It is thought that the vibrations from the aeroplane's engines during the long flight may have caused the damage.

Reproductions

In 1951, the Swiss publisher, Urs Graf-verlag Bern, produced a facsimile. The majority of the pages were reproduced in black and white photographs. There were, however, forty-eight pages reproduced in colour, including all of the full page decorations.

In 1974, Thames and Hudson, under licence from the Board of Trinity College Dublin, produced a facsimile edition of all the full page illustrations in the manuscript and a representative section of the ornamentation of the text pages. Also included are some enlarged details of the illustrations. These are all done in full colour. The photography was done by John Kennedy, Green Studio, Dublin.

In 1979, another Swiss publisher, Faksimile verlag Luzern, requested permission to produce a full colour facsimile of the book. Permission was initially denied because Trinity College officials felt that the risk of damage to the book was too high. In 1986, after developing a process which used gentle suction to straighten a page so that it could be photographed without touching it, the publisher was given permission to produce a facsimile edition. After each page was photographed, a single page facsimile was prepared and the colours were carefully compared to the original and adjustments were made where necessary. The facsimile was published in 1990 in two volumes, the facsimile and a volume of commentary by prominent scholars. One copy is held by the Anglican Church in Kells, on the site of the original monastery.

Description

The Book of Kells contains the four gospels of the Christian scriptures written in black, red, purple, and yellow ink in an insular majuscule script, preceded by prefaces, summaries, and concordances of gospel passages. Today it consists of 340 vellum leaves, called folios. The majority of the folios are part of larger sheets, called bifolios, which are folded in half to form two folios. The bifolios are nested inside of each other and sewn together to form gatherings called quires. On occasion, a folio is not part of a bifolio, but is instead a single sheet inserted within a quire.

It is believed that some 30 folios have been lost. (When the book was examined by Ussher in 1621 he counted 344 folios.) The extant folios are gathered into 38 quires. There are between four and twelve folios per quire (two to six bifolios). Ten folios per quire is common. Some folios are single sheets. The important decorated pages often occurred on single sheets. The folios had lines drawn for the text, sometimes on both sides, after the bifolia were folded. Prick marks and guide lines can still be seen on some pages. The vellum is of high quality, although the folios have an uneven thickness, with some being almost leather, while others are so thin as to be almost translucent. The book's current dimensions are 330 by 250 mm. Originally the folios were not of standard size, but they were cropped to the current standard size during an 18th century rebinding. The text area is approximately 250 by 170 mm. Each text page has 16 to 18 lines of text. The manuscript is in remarkably good condition considering its great age, though many pages have suffered some damage to the delicate artwork due to rubbing etc. The book must have been the product of a major scriptorium over several years, but was apparently never finished, the projected decoration of some of the pages appearing only in outline.

Contents

The book, as it exists now, contains preliminary matter, the complete text of the Gospels of Matthew, Mark and Luke, and the Gospel of John through John 17:13. The remainder of John and an unknown amount of the preliminary matter is missing and was perhaps lost when the book was stolen in the early 11th century. The extant preliminary matter consists of two fragments of lists of Hebrew names contained in the gospels, the Breves causae and the Argumenta of the four gospels, and the Eusebian canon tables. It is probable that, like the Lindisfarne Gospels and the Books of Durrow and Armagh, part of the lost preliminary material included the letter of Jerome to Pope Damasus I known as Novum opus, in which Jerome explains the purpose of his translation. It is also possible, though less likely, that the lost material included the letter of Eusebius to Carpianus, in which he explains the use of the canon tables. (Of all the insular gospels, only Lindisfarne contains this letter.)

Text and Script

The Book of Kells contains the text of the four gospels based on the Vulgate. It does not, however, contain a pure copy of the Vulgate. There are numerous variants from the Vulgate, where Old Latin translations are used rather than Jerome's text. Although these variants are common in all of the insular gospels, there does not seem to be a consistent pattern of variation amongst the various insular texts. It is thought that when the scribes were writing the text they often depended on memory rather than on their exemplar.

The manuscript is written in Insular majuscule, with some minuscule letters usually "c" and "s". The text is usually written in one long line across the page. Françoise Henry identified at least three scribes in this manuscript, whom she named Hand A, Hand B, and Hand C. Hand A is found on folios 1 through 19v, folios 276 through 289 and folios 307 through the end of the manuscript. Hand A for the most part writes eighteen or nineteen lines per page in the brown gall-ink common throughout the west. Hand B is found on folios 19r through 26 and folios 124 through 128. Hand B has a somewhat greater tendency to use minuscule and uses red, purple and black ink and a variable number of lines per page. Hand C is found throughout the majority of the text. Hand C also has greater tendency to use minuscule than Hand A. Hand C uses the same brownish gall-ink used by hand A, and wrote, almost always, seventeen lines per page.

Errors

There are a number of differences between the text and the accepted gospels. In the genealogy of Jesus, which starts at Luke 3:23, Kells erroneously names an extra ancestor. Matthew 10:34b should read “I came not to send peace, but the sword”. However rather than “gladium” which means “sword”, Kells has “gaudium” meaning “joy”. Rendering the verse in translation: “I came not [only] to send peace, but joy”.

Use

The book had a sacramental, rather than educational purpose. A large, lavish Gospel, such as the Book of Kells would have been left on the high altar of the church, and taken off only for the reading of the Gospel during Mass. However, it is probable that the reader would not actually read the text from the book, but rather recite from memory. It is significant that the Chronicles of Ulster state that the book was stolen from the sacristy (where the vessels and other accruements of the mass were stored) rather than from the monastic library. The design of the book seems to take this purpose in mind, that is the book was produced with appearance taking precedence over practicality. There are numerous uncorrected mistakes in the text. Lines were often completed in a blank space in the line above. The chapter headings that were necessary to make the canon tables usable were not inserted into the margins of the page. In general, nothing was done to disrupt the aesthetic look of the page: aesthetics were given a priority over utility.

Selected Source:

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Book_of_kells

The Book of Kells is an illuminated manuscript that has survived from the Middle Ages and has been described as the zenith of Western calligraphy and illumination. It contains the four gospels of the Bible in Latin, along with prefatory and explanatory matter decorated with numerous colourful illustrations and illuminations. Today it is on permanent display at the Trinity College Library in Dublin, Ireland.

Origin

The Book of Kells is the high point of a group of manuscripts in what is known as the Insular style produced from the late 6th through the early 9th centuries in monasteries in Ireland, Scotland and northern England and in continental monasteries with Irish or English foundations. These manuscripts include the Cathach of St. Columba, the Ambrosiana Orosius, a fragmentary gospel in the Durham cathedral library (all from the early 7th century), and the Book of Durrow (from the second half of the 7th century). From the early 8th century come the Durham Gospels, the Echternach Gospels, the Lindisfarne Gospels (see illustration at right), and the Lichfield Gospels. The St. Gall Gospel Book and the Macregal Gospels come from the late 8th century. The Book of Armagh (dated to 807–809), the Turin Gospel Book Fragment, the Leiden Priscian, the St. Gall Priscian and the Macdurnan Gospel all date from the early 9th century. Scholars place these manuscripts together based on similarities in artistic style, script, and textual traditions. The fully developed style of the ornamentation of the Book of Kells places it late in this series, either from the late eighth or early ninth century. The Book of Kells follows many of the iconographic and stylistic traditions found in these earlier manuscripts. For example, the form of the decorated letters found in the incipit pages for the Gospels is surprisingly consistent in Insular Gospels. Compare, for example, the incipit pages of the Gospel of Matthew in the Lindisfarne Gospels and in the Book of Kells both of which feature intricate decorative knotwork inside the outlines formed by the enlarged initial letters of the text.

The name "Book of Kells" is derived from the Abbey of Kells in Kells, County Meath in Ireland, where it was kept for much of the medieval period. The date and place of production of the manuscript has been the subject of considerable debate. Traditionally, the book was thought to have been created in the time of Columba (also known as St Columcille), possibly even as the work of his own hands. However, it is now generally accepted that this tradition is false based on palaeographic grounds: the style of script in which the book is written did not develop until well after Columba's death, making it impossible for him to have written it. Evidence shows the Book of Kells was written around the year 800 AD. There is another tradition which has some traction among Irish scholars which suggests that it was created for the 200th anniversary of the saint's death.

The manuscript was never finished. There are at least five competing theories about the manuscript's place of origin and time of completion. First, the book may have been created entirely at Iona, then brought to Kells and never finished. Second, the book may have been begun at Iona and continued at Kells, but never finished. Third, the manuscript may have been produced entirely in the scriptorium at Kells. Fourth, it may have been produced in the north of England, perhaps at Lindisfarne, then brought to Iona and from there to Kells. Finally, it may have been the product of an unknown monastery in Scotland. Although the question of the exact location of the book's production will probably never be answered conclusively, the second theory, that it was begun at Iona and finished at Kells, is currently the most widely accepted. Regardless of which theory is true, it is certain that the Book of Kells was produced by Columban monks closely associated with the community at Iona.

Medieval Period

The evidence for an eleventh century presence of the book in Kells consists of an entry in the Annals of Ulster for 1009. This entry records that "the great Gospel of Columkille, the chief relic of the Western World, was wickedly stolen during the night from the western sacristy of the great stone church at Cenannas on account of its wrought shrine". Cenannas is the Irish name for Kells. The manuscript was recovered a few months later - minus its golden and bejewelled cover - "under a sod". It is generally assumed that the "great Gospel of Columkille" is the Book of Kells. If this is correct, then the book was in Kells by 1009, and been there long enough for thieves to learn of its presence. The force of ripping the manuscript free from its cover may account for the folios missing from the beginning and end of the Book of Kells.

Regardless, the book was certainly at Kells in the 12th century, when land charters pertaining to the Abbey of Kells were copied into some of the book's blank pages. The copying of charters into important books such as the Book of Kells was a wide-spread mediaeval practice, which gives us indisputable evidence about the location of the book at the time the charters were written into it.

The Abbey of Kells was dissolved due to the ecclesiastical reforms of the 12th century. The abbey church was converted to a parish church in which the Book of Kells remained.

Book of Kildare

The 12th century writer, Gerald of Wales, in his Topographia Hibernica, described, in a famous passage, seeing a great Gospel Book in Kildare which many have since assumed was the Book of Kells. The description certainly matches Kells:

"This book contains the harmony of the Four Evangelists according to Jerome, where for almost every page there are different designs, distinguished by varied colours. Here you may see the face of majesty, divinely drawn, here the mystic symbols of the Evangelists, each with wings, now six, now four, now two; here the eagle, there the calf, here the man and there the lion, and other forms almost infinite. Look at them superficially with the ordinary glance, and you would think it is an erasure, and not tracery. Fine craftsmanship is all about you, but you might not notice it. Look more keenly at it and you will penetrate to the very shrine of art. You will make out intricacies, so delicate and so subtle, so full of knots and links, with colours so fresh and vivid, that you might say that all this was the work of an angel, and not of a man."

Since Gerald claims to have seen this book in Kildare, he may have seen another, now lost, book equal in quality to the Book of Kells, or he may have misstated his location.

Modern Period

The Book of Kells remained in Kells until 1654. In that year Cromwell's cavalry was quartered in the church at Kells and the governor of the town sent the book to Dublin for safe keeping. The book was presented to Trinity College in Dublin in 1661 by Henry Jones, who was to become bishop of Meath after the Restoration. The book has remained at Trinity College since the 17th century, except for brief loans to other libraries and museums. It has been displayed to the public in the Old Library at Trinity since the 19th century.

In the 16th century, the chapter numbers of the Gospels according to the division created by the 13th century Archbishop of Canterbury, Stephen Langton were written in the margins of the pages in roman numerals by Gerald Plunkett of Dublin. In 1621 the folios were numbered by the bishop-elect of Meath, James Ussher. In 1849 Queen Victoria and Prince Albert were invited to sign the book. They in fact signed a modern flyleaf which was erroneously believed to have been one of the original folios. The page which they signed was removed when the book was rebound in 1953.

Over the centuries the book has been rebound several times. During an 18th century rebinding, the pages were rather unsympathetically cropped, with small parts of some illustrations being lost. The book was also rebound in 1895, but that rebinding broke down quickly. By the late 1920s several folios were being kept loose under a separate cover. In 1953, the work was bound in four volumes by Roger Powell, who also gently stretched several of the pages, which had developed bulges.

In 2000, the volume containing the Gospel of Mark was sent to Canberra, Australia for an exhibition of illuminated manuscripts. This was only the fourth time the Book of Kells had been sent abroad for exhibition. Unfortunately, the volume suffered what has been called "minor pigment damage" while en route to Canberra. It is thought that the vibrations from the aeroplane's engines during the long flight may have caused the damage.

Reproductions

In 1951, the Swiss publisher, Urs Graf-verlag Bern, produced a facsimile. The majority of the pages were reproduced in black and white photographs. There were, however, forty-eight pages reproduced in colour, including all of the full page decorations.

In 1974, Thames and Hudson, under licence from the Board of Trinity College Dublin, produced a facsimile edition of all the full page illustrations in the manuscript and a representative section of the ornamentation of the text pages. Also included are some enlarged details of the illustrations. These are all done in full colour. The photography was done by John Kennedy, Green Studio, Dublin.

In 1979, another Swiss publisher, Faksimile verlag Luzern, requested permission to produce a full colour facsimile of the book. Permission was initially denied because Trinity College officials felt that the risk of damage to the book was too high. In 1986, after developing a process which used gentle suction to straighten a page so that it could be photographed without touching it, the publisher was given permission to produce a facsimile edition. After each page was photographed, a single page facsimile was prepared and the colours were carefully compared to the original and adjustments were made where necessary. The facsimile was published in 1990 in two volumes, the facsimile and a volume of commentary by prominent scholars. One copy is held by the Anglican Church in Kells, on the site of the original monastery.

Description

The Book of Kells contains the four gospels of the Christian scriptures written in black, red, purple, and yellow ink in an insular majuscule script, preceded by prefaces, summaries, and concordances of gospel passages. Today it consists of 340 vellum leaves, called folios. The majority of the folios are part of larger sheets, called bifolios, which are folded in half to form two folios. The bifolios are nested inside of each other and sewn together to form gatherings called quires. On occasion, a folio is not part of a bifolio, but is instead a single sheet inserted within a quire.

It is believed that some 30 folios have been lost. (When the book was examined by Ussher in 1621 he counted 344 folios.) The extant folios are gathered into 38 quires. There are between four and twelve folios per quire (two to six bifolios). Ten folios per quire is common. Some folios are single sheets. The important decorated pages often occurred on single sheets. The folios had lines drawn for the text, sometimes on both sides, after the bifolia were folded. Prick marks and guide lines can still be seen on some pages. The vellum is of high quality, although the folios have an uneven thickness, with some being almost leather, while others are so thin as to be almost translucent. The book's current dimensions are 330 by 250 mm. Originally the folios were not of standard size, but they were cropped to the current standard size during an 18th century rebinding. The text area is approximately 250 by 170 mm. Each text page has 16 to 18 lines of text. The manuscript is in remarkably good condition considering its great age, though many pages have suffered some damage to the delicate artwork due to rubbing etc. The book must have been the product of a major scriptorium over several years, but was apparently never finished, the projected decoration of some of the pages appearing only in outline.

Contents

The book, as it exists now, contains preliminary matter, the complete text of the Gospels of Matthew, Mark and Luke, and the Gospel of John through John 17:13. The remainder of John and an unknown amount of the preliminary matter is missing and was perhaps lost when the book was stolen in the early 11th century. The extant preliminary matter consists of two fragments of lists of Hebrew names contained in the gospels, the Breves causae and the Argumenta of the four gospels, and the Eusebian canon tables. It is probable that, like the Lindisfarne Gospels and the Books of Durrow and Armagh, part of the lost preliminary material included the letter of Jerome to Pope Damasus I known as Novum opus, in which Jerome explains the purpose of his translation. It is also possible, though less likely, that the lost material included the letter of Eusebius to Carpianus, in which he explains the use of the canon tables. (Of all the insular gospels, only Lindisfarne contains this letter.)

Text and Script

The Book of Kells contains the text of the four gospels based on the Vulgate. It does not, however, contain a pure copy of the Vulgate. There are numerous variants from the Vulgate, where Old Latin translations are used rather than Jerome's text. Although these variants are common in all of the insular gospels, there does not seem to be a consistent pattern of variation amongst the various insular texts. It is thought that when the scribes were writing the text they often depended on memory rather than on their exemplar.

The manuscript is written in Insular majuscule, with some minuscule letters usually "c" and "s". The text is usually written in one long line across the page. Françoise Henry identified at least three scribes in this manuscript, whom she named Hand A, Hand B, and Hand C. Hand A is found on folios 1 through 19v, folios 276 through 289 and folios 307 through the end of the manuscript. Hand A for the most part writes eighteen or nineteen lines per page in the brown gall-ink common throughout the west. Hand B is found on folios 19r through 26 and folios 124 through 128. Hand B has a somewhat greater tendency to use minuscule and uses red, purple and black ink and a variable number of lines per page. Hand C is found throughout the majority of the text. Hand C also has greater tendency to use minuscule than Hand A. Hand C uses the same brownish gall-ink used by hand A, and wrote, almost always, seventeen lines per page.

Errors

There are a number of differences between the text and the accepted gospels. In the genealogy of Jesus, which starts at Luke 3:23, Kells erroneously names an extra ancestor. Matthew 10:34b should read “I came not to send peace, but the sword”. However rather than “gladium” which means “sword”, Kells has “gaudium” meaning “joy”. Rendering the verse in translation: “I came not [only] to send peace, but joy”.

Use

The book had a sacramental, rather than educational purpose. A large, lavish Gospel, such as the Book of Kells would have been left on the high altar of the church, and taken off only for the reading of the Gospel during Mass. However, it is probable that the reader would not actually read the text from the book, but rather recite from memory. It is significant that the Chronicles of Ulster state that the book was stolen from the sacristy (where the vessels and other accruements of the mass were stored) rather than from the monastic library. The design of the book seems to take this purpose in mind, that is the book was produced with appearance taking precedence over practicality. There are numerous uncorrected mistakes in the text. Lines were often completed in a blank space in the line above. The chapter headings that were necessary to make the canon tables usable were not inserted into the margins of the page. In general, nothing was done to disrupt the aesthetic look of the page: aesthetics were given a priority over utility.

Selected Source:

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Book_of_kells